Blog

Relationships in the early years

Kirsten Asmussen answers key questions from professionals about innovation, commissioning decisions and workforce qualifications.

This article was first published by Children & Young People Now, February 2017.

The Early Intervention Foundation (EIF) has held seminars to share findings from Foundations for Life – its 2016 review of early years parenting support – with commissioners, practitioners and policymakers. The review marked the first time EIF used its own methods to assess the strength of evidence and costs of 75 interventions developed to support parent-child interaction during the first five years of life. Of these, 17 were assessed as being “evidence-based”, meaning that there was sufficiently strong evidence linking benefits for parents and children to the programme.

In addition to describing the interventions in detail, the seminars enabled EIF to respond to key issues raised by professionals, three of which are outlined below.

1. What scope is there for innovation in parenting interventions given the desire for the highest level of evidence?

The review identified areas where evidence-based options exist, areas where evidence-based interventions may not be necessary, and areas where innovation could be useful.

Of the 17 evidence-based interventions identified in the EIF review:

- Ten had evidence of reducing noncompliant behaviour in a child aged three plus where there is a pre-identified behavioural issue.

- Five had evidence of improving children’s attachment security.

- Four of these programmes are designed to be offered antenatally or during the child’s first year.

Two had evidence of supporting learning outcomes in children aged three to five. But a broader literature review suggests a strong need for evidence-based options for supporting learning outcomes of disadvantaged children. The review also found that behavioural interventions offered to families with young children (30 months or younger) were less likely to be effective.

These findings suggest there is already a good choice of evidence-based interventions targeting behavioural problems in children aged three to five. However, innovation and evaluation is still needed to develop programmes that support the early learning of disadvantaged young children.

2. How should the findings be used to inform commissioning or decommissioning decisions?

Knowledge about the strength of an intervention’s evidence is a useful starting point for making commissioning decisions. But evidence should never be the sole basis for selecting an intervention.

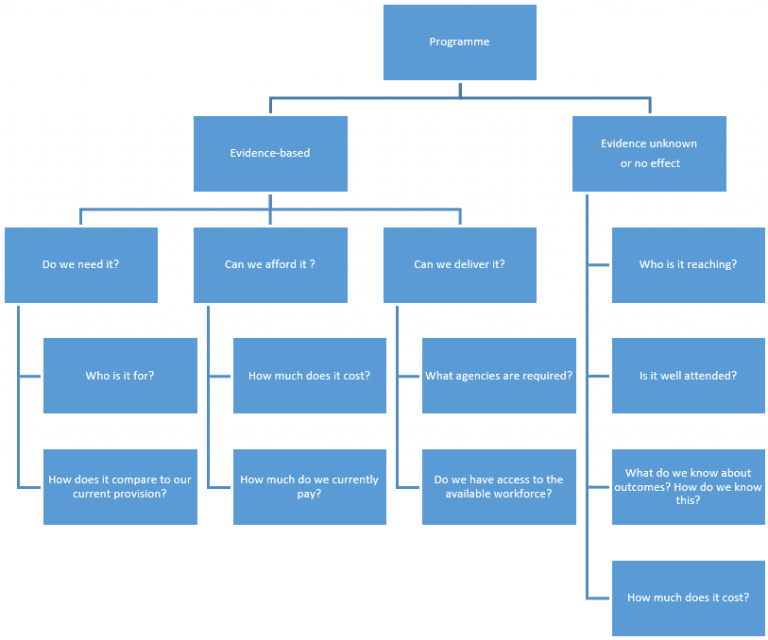

Commissioning decisions should be informed by various factors, including local needs, and the quality and costs of provision. For evidence-based interventions this starts with whether it is needed, affordable and deliverable.

Questions to consider when commissioning/decommissioning interventions

Deciding to decommission a service should be straightforward when it is clear that the provision is unsatisfactory. Decommissioning decisions are more difficult when current provision appears to be working. In these instances, commissioners should carefully consider the impact of their provision on child outcomes. Ways to do this include:

- Careful assessment of individual family case files

- Pre/post evaluations utilising validated measures of outcomes

- Monitoring data that tracks children’s post-intervention progress through services.

If there are positive indications that services are providing benefits for children, decommissioning may not be necessary. However, if the benefits of services remain unclear, commissioners should consider other, more evidence-based, options.

3. How can interventions be delivered if practitioners with a suitable advanced qualification are not available?

The majority of interventions identified as evidence-based in the EIF review are intended to be delivered by practitioners with a Bachelor’s qualification or higher in teaching, health visiting, psychology or social work. This is because:

- Practitioner training for the majority of programmes is short and often assumes previous knowledge of child development and working with families.

- All the review programmes aim to improve children’s wellbeing through support delivered to parents. As such, they are a form of child mental health and require a skilled practitioner to develop a positive working relationship with the parent.

- Those attending parenting interventions often do so because of serious concerns, meaning that disclosures of abuse and neglect are not uncommon. Practitioners need a good understanding of how to respond to these disclosures and report them.

- The lack of a suitably qualified workforce makes it tempting to have under-qualified practitioners deliver parenting interventions.

We discourage this for several reasons. First, many studies have found that interventions lose their effectiveness, and in some cases cause harm, when delivered by under-qualified staff. Second, practitioners can become frustrated when implementing interventions that are beyond their skills, and interventions are quickly abandoned.

Well conducted workforce audits can help commissioners identify appropriately qualified staff by:

- Uncovering resources that were previously unknown.

- Identifying staff who may benefit from training that will provide them with the skills to deliver parenting interventions.

- Helping commissioners to understand where various skills exist and to realign resources.

- Where shortfalls in appropriately qualified staff exist, commissioners should recruit externally.