Blog

Children's development and family circumstances: Exploring the SEED data

EIF senior economist William Teager presents some findings from our analysis of the new longitudinal Study of Early Education and Development (SEED) data, looking at the relationships between children's development and behaviour outcomes, and the home learning environment, region of the country, family circumstances, and mothers' mental health and education.

The Study of Early Education and Development (SEED) is a new longitudinal cohort study, funded by the Department for Education. The purpose of the study is to evaluate the impact of early education provision on children’s outcomes. The survey, delivered by a consortium of researchers, is following a cohort of children from age 2 through to the end of key stage 1 at age 7. Data from the first two waves, for children aged 2 and 3, has recently been made available.[1]

In addition to data collected on the type of childcare received, the SEED study collects rich information on the structure of households, their economic circumstances, and the quality of parenting and the home learning environment. A formal evaluation of the impact of childcare, using the SEED study, is being carried out by Oxford University. They have already published compelling findings from this work, particularly on the impact of early education on developmental outcomes at age 3.

The SEED survey provides a valuable new resource for further research into the drivers and potential mitigating factors that explain why some children fall behind. Here, we present some interesting findings from our own initial investigations into the data, focusing on some fresh associations between children’s background characteristics, early life experiences and developmental outcomes.

All outcome variables have been standardised for ease of comparison. This means that for each outcome measure the population of children is compared with the average, where a positive score indicates above average performance for that group and a negative result indicates below average performance.[2]

Early speech and language development

EIF’s review of the evidence on the impact of early language acquisition has shown that it is a vital part of young children’s development. According to this previous research, it contributes to their ability to manage emotions and communicate feelings, to establish and maintain relationships, and to learn to read and write. Children from socially disadvantaged families are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with a language problem. Furthermore, the high prevalence of language problems among disadvantaged children is also thought to contribute to the achievement gap that exists by the time children enter school and which persists until they leave.

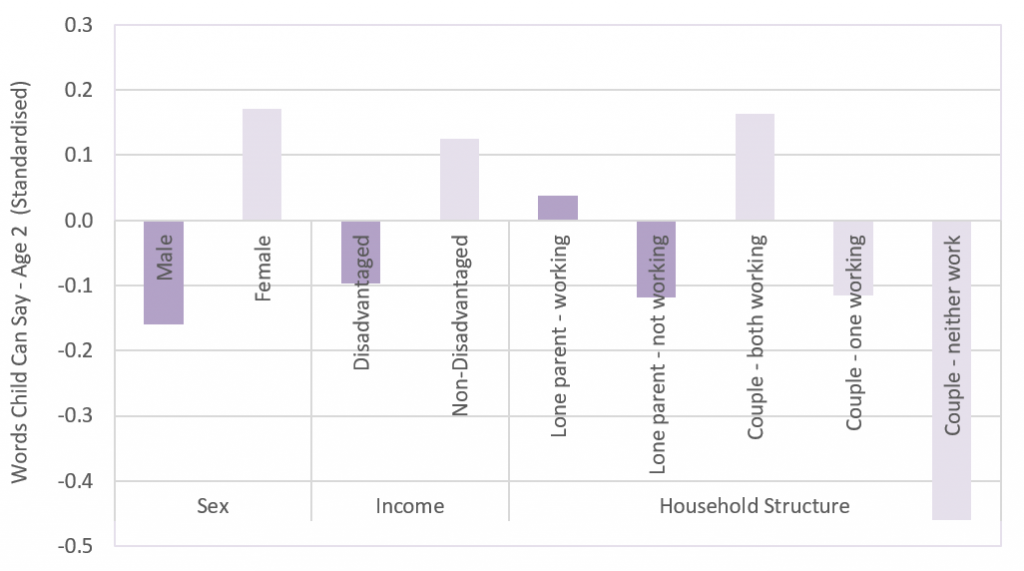

Figure 1: Household and child-level characteristics and early language acquisition

Figure 1 shows the relationships found at age 2 between various child and household characteristics and early language acquisition. There are clearly large language differences that emerge early in childhood that open across various dimensions of gender, income[3] and household structure. In a finding that is consistent with EIF’s previous reviews, this analysis indicates that children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are likely to have significantly worse early language acquisition than children from more advantaged backgrounds. Interestingly, a child’s sex appears to have a greater impact than household income, with boys performing significantly worse than girls.

Turning to household structure, there is no simple relationship with household structure or parents’ working status. Children from working households perform better than the average child; this holds whether parents are together or separated, although the effect is stronger in couple households.

Reading to children

The role disadvantage plays in combination with other factors is important in order to understand differences in the developmental trajectories of children raised in low- and high-income households. Hart and Risley’s ‘30 million word gap’ study observed that American toddlers growing up in low-income households heard approximately 600 words per hour, while those from professional families heard more than 2,100 words per hour.[4]

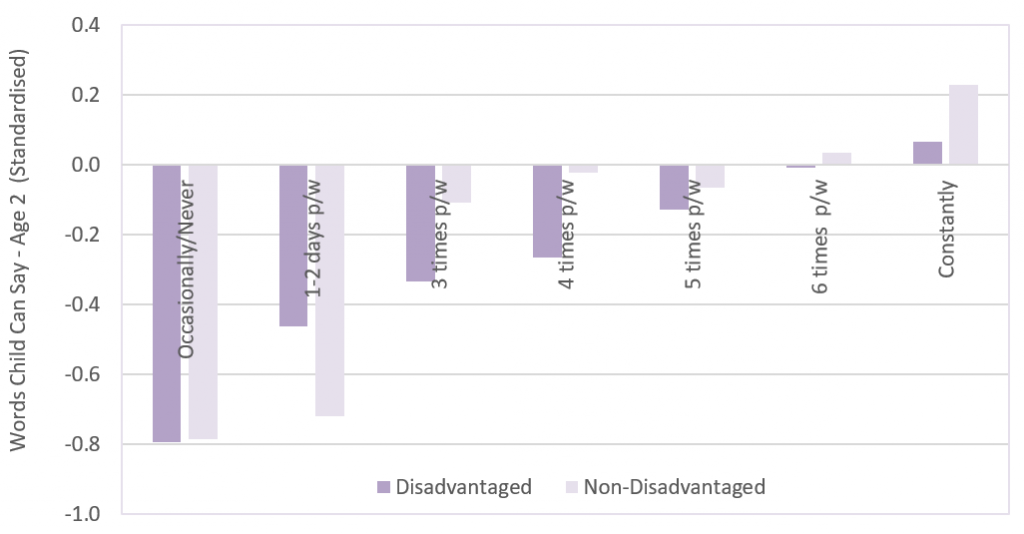

Figure 2: Reading to child at age two and early language acquisition

Figure 2 shows the association between the frequency that parents report reading to their child in the SEED survey and early language development. Regardless of the level of disadvantage there is a strong association between frequency of reading and early language development.

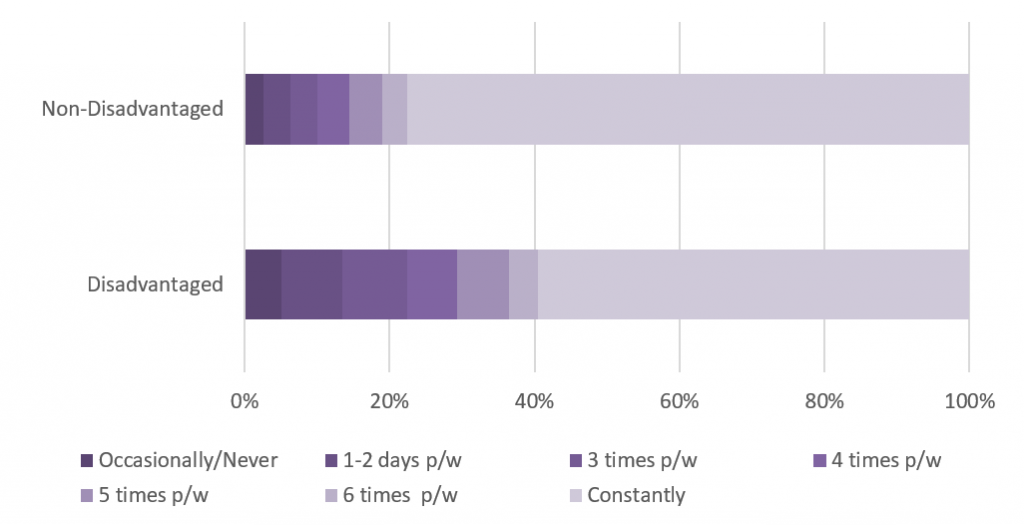

Interestingly, when we look at the frequency parent’s report reading to their children by level of disadvantage, both the majority of disadvantaged households (those in the bottom 40% of the income distribution) and non-disadvantaged households report reading at least seven times a week to their child (as shown in figure 3). Disadvantaged households do report reading to their children less, however this reported difference is perhaps smaller than we might assume, based on the findings of Hart and Risley. While this self-reported measure does not reflect the duration or quantity of time spent reading, at face value, differences in reading frequency explain only a small proportion of the gap in early word recognition.

Figure 3: Frequency of reading to child

Regional variation

There has been much interest in the regional variation in school performance – and in particular, in the higher academic achievement of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds in London, compared to pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds nationally. Analysis by the IFS has shown that disadvantaged children in London actually perform worse on some measures of vocabulary at age 3, compared with children outside the capital. However, between the between the ages of 5 and 11 disadvantaged children in London show faster rates of academic progression.

The SEED study provides some opportunity to look at this again. In a finding that aligns with that of the IFS, our analysis indicates that early language acquisition at age 2 appears to be worse in London, compared to disadvantaged children in all other regions nationally, as shown in figure 4. We find a similar pattern when looking at children’s naming vocabulary at age 3, where disadvantaged children in London perform worse than disadvantaged children elsewhere in the country.

Figure 4: Regional variation in language acquisition

On the other measures of child development at age 2 and 3 contained in the SEED survey, there is a more mixed picture. And, as the recent report published by the Children’s Commissioner has highlighted, London children are outperforming pupils in the north of England in terms of meeting the expected standards of the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile.

However, as far as early language acquisition is predictive of later school attainment, this provides some supporting evidence that the apparent ‘London effect’ – the tendency for disadvantaged pupils in the capital to perform better than those nationally – may in part be explained by regional differences in home or school factors that influence children’s development during their school-age years.

The impact of mothers’ education and mental health

Previous analysis published by the EIF highlighted the prevalence of behavioural and emotional problems among children, and the crucial role played by mothers’ mental health and levels of education. This previous work used longitudinal data on a cohort of children born in the 1970s (the Birth Cohort Study), to analyse the drivers of childhood behavioural problems (as measured on the Rutter scale). It confirmed the strong socioeconomic gradient associated with childhood behavioural problems, where children from low socioeconomic status households were found to exhibit greater behavioural and emotional difficulties.

Further analysis showed this to be explained almost fully by maternal mental health and levels of parental education. This suggests it may be the fact that poor mental health is highly associated with economic disadvantage, rather than purely economic disadvantage itself, that is adversely driving worse outcomes for these children. Furthermore, the link between poor maternal mental health and behavioural problems in children was found to be strongest in the poorest households, suggesting there may be some protective factors associated with being in a better-off household.

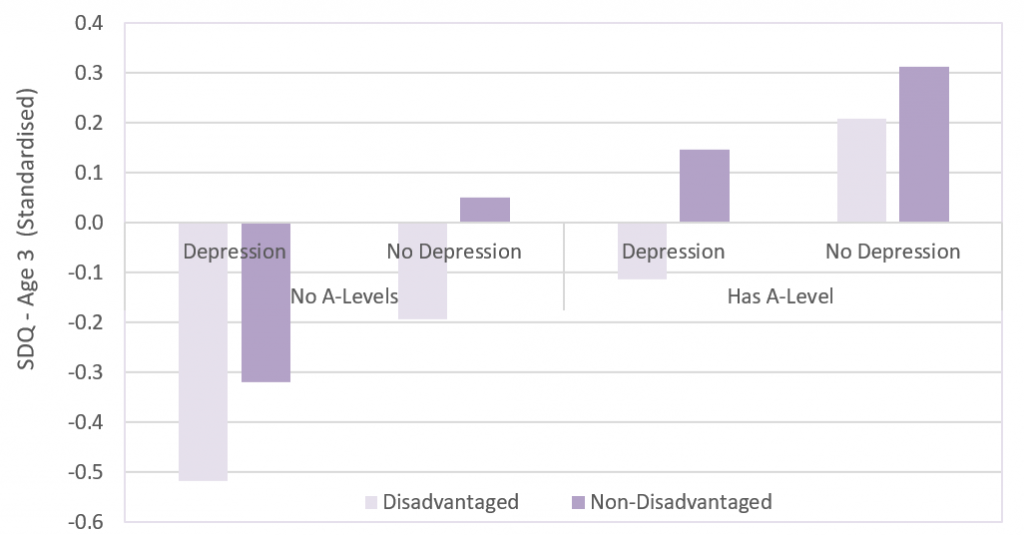

Data from the SEED study allows us to consider these relationships again, for a more recent cohort of children. In figure 5, we have used indicators on whether mothers have ever visited a GP for depression or anxiety – as a proxy for their mental health – and data on whether or not mothers have at least achieved the equivalent of A-levels as their highest qualification. To consider the impact on child behavioural and emotional problems, we have used parents’ ratings of their children on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ).[5]

Figure 5: Average SDQ scores by mother’s highest qualification and mental health indicator

Figure 5 shows similar findings to those reported from our previous analysis using the BCS data. That is:

- There is a strong socioeconomic gradient associated with childhood behavioural development and level of disadvantage. Children from economically disadvantaged households perform worse on parent-reported SDQ at age 3 compared to similar children, controlling for maternal qualifications and mental health.

- Both depression (as measured by whether mothers have ever visited a GP for depression or anxiety) and parental qualifications (as measured by whether mothers have achieved at least the equivalent of A-levels) are strong predictors of child behavioural development.

- Being from a higher-income household appears to be associated with some offsetting factors against the negative effects of maternal depression and low levels of qualifications.

Where the results differ from our previous analysis is that controlling for depression and qualifications alone does not appear to fully explain the disparity in behavioural development between children from low- and high-income households. These results are purely descriptive, and for some sub-groups, based on relatively small sample sizes, making it hard to draw strong conclusions. However, the results may suggest some change over the four decades since the BCS in the routes through which economic deprivation affects outcomes for children. As future waves of the SEED data are released, it would be useful to consider the persistence of these effects in more depth.

What happens next?

It is important that DfE continues to invest in new longitudinal cohort studies. As future waves are added, the SEED survey will help build our understanding of the drivers of early childhood development. The descriptive findings presented here are broadly in line with previous reports we have published, namely in drawing out the significance of family characteristics, economic circumstances and the home learning environment in explaining the variation in early childhood development. Much of this variation remains unexplained, however, and we encourage the research community to make further use of this rich dataset.

Notes

1. NatCen Social Research, University of Oxford, Department of Education. (2017). Study of Early Education and Development: Wave 1, 2013-2014. [data collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 8277, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8277-1; NatCen Social Research, University of Oxford, Department of Education. (2017). Study of Early Education and Development: Wave 2, 2014-2015. [data collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 8278, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8278-1 ^back

2. Standardising variables allows for comparison of outcomes measured on different scales. Variables are rescaled to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. In interpreting, children reported to have a negative mean standardised score will be performing below the average for all children on a particular measure, and a child with a positive standardised score will be performing above the average for all children on that measure. ^back

3. DfE’s eligibility criteria for the 2-year-old free childcare offer is used to categorise households by income. Disadvantage households are those whose income is than £16,190 a year (as measured by HMRC’s gross taxable income definition), equivalent to approximately 40% of lowest earning households. ^back

4. Hart, B., and Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul Brookes. ^back

5. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a self or parent/practitioner reported behavioural screening questionnaire for children and adolescents ages 2 through 17 years. Total SDQ scores are usually negatively framed, that is, low scores are associated with less risk of behavioural problems. For ease of exposition, we have reversed the axis here, so higher scores are associated with less risk of behavioural issues. ^back