Blog

Facing up to the unequal economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic

As the nation cautiously turns towards Covid recovery, it is important to recognise, understand and respond to the ways in which the pandemic has impacted on the lives of different groups in society. In this guest blog, Dr Andrea Barry, senior analyst at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), looks at how the consequences of pandemic life have fallen on minority ethnic groups and different family types in particular.

As the pandemic raged on, JRF and other organisations raised the alarm on the unequal impact of the pandemic on people in poverty. In June 2020, JRF published a report highlighting the high levels of child poverty in the UK, the strain on parents who were in the midst of an unprecedented lockdown and change of circumstance, and the difficulty some parents were facing in providing food and shelter for their families. It is essential to understand where these inequities have originated and how they will continue unless we act.

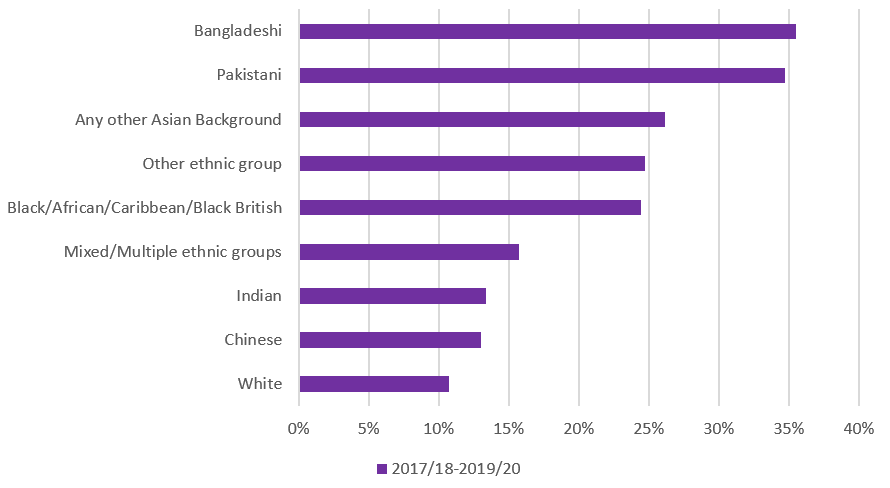

For certain UK minority ethnic groups, poverty rates are exceedingly high, which put them at a significant disadvantage during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, Black, Asian and minority ethnic workers were more likely to experience poverty while in work and were over-represented in lower-paid positions in low-paid sectors. In-work poverty rates are higher for Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups, but especially for Bangladeshi and Pakistani workers, which means they entered the crisis much more susceptible to its effects.

Figure 1: Bangladeshi and Pakistani workers have the highest rates of in-work poverty

Source: JRF analysis of Households Below Average Income and Family Resources Survey, 2019/20

Source: JRF analysis of Households Below Average Income and Family Resources Survey, 2019/20

JRF research estimates that Pakistani and Bangladeshi workers are one of the groups most at risk of job losses as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme winds down.

Furthermore, these groups have the lowest average hourly pay, under £11, compared to other groups. Pakistani and Bangladeshi workers are more likely to work in catering, restaurants and related businesses, as well as in taxi driving and chauffeuring. Nearly one in three Bangladeshi men work in catering, restaurants and related businesses, compared to 1 in 100 White British men. Similarly, only 1 in 100 White British men work in taxi, chauffeuring and related businesses, compared to one in seven Pakistani men.

This can be seen in a substantial ethnicity pay gap. According to research by the Runnymede Trust, when comparing two graduate men, one Black and the other White, working in the same job in the same region with the same education, the Black male worker earns 17% less than the White male worker. This wide pay gap holds back Black, Asian, and minority ethnic workers from trying to progress and break free from poverty through good jobs.

Furthermore, these employment patterns have increased the risk of losing earnings or jobs during the pandemic. Evidence shows deep stress on workers in jobs that could not easily be done from home. According to JRF research, these jobs that require close contact to others were at the biggest risk for redundancies. As such, some minority ethnic groups – such as Bangladeshi and Pakistani communities, who already faced heightened health risks from the pandemic – were twice as likely to have a job at risk of redundancy compared to the White population. At the beginning of the pandemic, Black, Asian, and minority ethnic workers were 13% less likely to be furloughed, but 14% more likely to be made unemployed.

Understanding these differences in circumstances and consequences is an essential part of identifying responses that can help all families to recover.

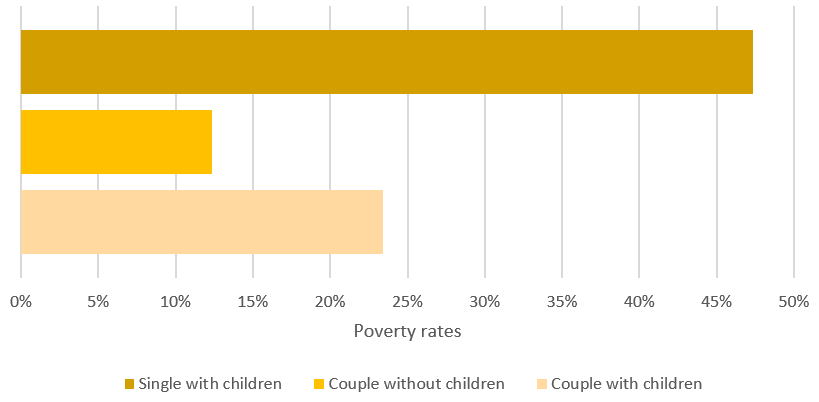

Other important patterns emerge when we look at different family types. Here, poverty rates are higher for families with children. For single parents, their poverty rates are the highest, at 47%, compared to couples with children (23%).

Figure 2: Poverty rates are higher for families with children

Source: JRF Analysis of Households Below Average Income, 2019/20

Source: JRF Analysis of Households Below Average Income, 2019/20

Single parents have seen an increase in employment levels over the last 25 years, from just over 40% in 1996 to 70% in 2019. However, even with increasing employment rates, their poverty rates and in-work poverty rates remain high.

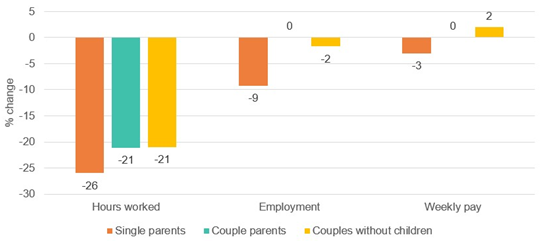

Worryingly, the pandemic hit single parents hard, with an immediate drop in employment rates. Before the pandemic, single parents were more likely to be stuck in low pay, affecting one in three compared to only 8% of fathers in couples and 18% of mothers in couples. In the first two months of the pandemic, single parents saw a larger impact on hours, employment and pay. Overall, single parents were struggling pre-Covid and this continued during the pandemic.

Unfortunately, families all over the UK were struggling. According to JRF research, 86% of families with children on Universal Credit or Child Tax Credits reported additional costs in the pandemic, with the highest extra costs including food, heating, electricity and/or water. Many families on UC or CTC were not eligible for free school meals and feeding children during the pandemic created an extra financial hurdle.

Figure 3: Single parents with children saw the biggest economic impact as a result of the pandemic

Source: Dromey, J., Dewar, L. & Finnegan, J. (2020). Tackling single parent poverty after coronavirus, Learning and Work Institute, Gingerbread and JRF. https://www.gingerbread.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Tackling-single-parent-poverty-after-coronavirus.pdf

Source: Dromey, J., Dewar, L. & Finnegan, J. (2020). Tackling single parent poverty after coronavirus, Learning and Work Institute, Gingerbread and JRF. https://www.gingerbread.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Tackling-single-parent-poverty-after-coronavirus.pdf

Why does this matter? These inequities can put significant additional stress on parents, and on their children in turn.

Those in persistent poverty have a three times higher risk of mental ill health. Ill mental health is more strongly associated with poverty in late childhood. Compared to those who have never experienced poverty, any period of poverty is associated with worse mental health in early adolescence. So rising levels of poverty will have a detrimental impact on children’s mental health, which tracks from early life to adulthood.

The effects of parental stress have an impact on children, especially children who deal with the cumulative effects of poverty, exclusion and discrimination. Racism and inequities contribute significantly, with children from UK minority ethnic groups dealing with societal pressures in addition to the consequences of these inequities.

There are long-term economic impacts to consider as well. We know from JRF’s work in partnership with people with experience of in-work poverty that low-paid jobs are too often unpredictable and insecure, or fail to provide people with dignity and respect at work. There is substantial research on the link between parents’ labour market outcomes and children’s future prospects. So it is imperative to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty and poorer labour market outcomes between parents and children.

All of the worst factors of stress and mental health have deteriorated during the pandemic – right across society, but for some families in particular. Providing suitable post-pandemic support requires an understanding of how this challenging period has affected different families in different ways. Moreover, given the context of more children living in poverty, it is imperative that we do all that we can to address the causes and consequences of poverty in the UK.