Blog

Is your local early help offer helping families? Six principles to help you find out

EIF head of local evaluation Sarah Taylor sets out the six principles for evaluating complex, multi-agency early help systems.

All local areas want to prove that their early help offer is helping families, but do you know how to do this? One of the most common requests we receive at EIF is for support and advice on how to evaluate. Our new guidance on evaluating the impact of early help adds to our growing set of resources on this question.

We worked with local areas who were trying to evaluate their early help services, to develop a set of principles. Applying these can help to build an evidence culture and make services easier to evaluate, as part of a business-as-usual cycle of learning and improvement. (If there is a specific programme you wish to evaluate, you should instead consult our other new guide, 10 steps for evaluation success.)

Evaluation of complex multi-agency systems with many components is possible. But it is not easy, especially given the scarcity of time and capability in busy services.

It is important to fill the gap. As Donna Molloy set out in her blog on early help this week, there is currently a lack of evaluation of early help systems that we would consider robust. This makes it more difficult to make the case for investment in early help locally and nationally. It also makes it difficult to know what approaches are most promising. Commissioners and service managers may be making decisions and working in the dark.

We aim to shed some light, to help local areas make some much-needed progress in filling the gaps in the evidence base for early intervention in the UK. We believe the six principles set out in this guide can help managers and commissioners to find out what difference they are making for families.

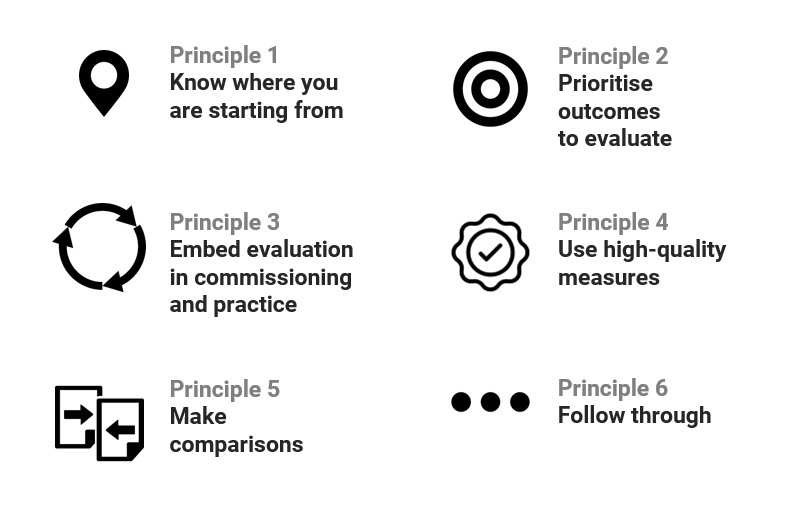

Principle 1: Know where you are starting from

You need a good understanding of local families if you are to evaluate the services they receive. Involve your partners so that you can set out the whole system and understand how all local activities contribute to outcomes. Your needs assessment should go beyond describing needs at a point in time to consider pathways of needs – how needs change over time for different families, strengths (such as strong relationships), and patterns of service use.

You also need to understand the inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes of your local offer, and the assumptions and external factors on which these depend, as part of a logic model. One way to build your understanding is through system-mapping of relationships and pathways. Consider making changes to data systems in order to track families and capture links between services.

Principle 2: Prioritise outcomes to evaluate

Set the scope of your evaluation by defining where the boundaries of your early help system lie. You and your partners in the early help system should only evaluate the outcomes for which you are accountable. Many local areas have broad aims, such as better outcomes, improved user experience and reduced costs. Clearly defined aims give you something concrete to evaluate. Your aims should be realistic, and you should limit yourself to a manageable number of aims.

Principle 3: Embed evaluation in commissioning and practice

See evaluation as part of commissioning, not as a one-off activity. Aim to invest in evidence capacity as part of continuing professional development: upskill staff on how to gather, understand and interpret data for evaluations. Demonstrate leadership by using evidence, and grow an evidence culture across the system. Prioritise investment in evaluation as part of commissioning. One rule of thumb is to assign at least 10% of a programme’s budget to evaluation.

Principle 4: Use high-quality measures

Exploit existing sources of routinely collected data on outcomes, and only gather data yourself where these sources are not available. If you do gather your own data, use measures that have been carefully developed by experts. Measures should be valid and reliable, relevant and responsive; reasonable in terms of length, simplicity and accessibility; allow you to track distance travelled or progress; and broad enough for use with a range of families. Consider upgrading data systems and changing working practices to introduce a shared ID, such as a unique pupil number or NHS number, for all partners to use.

Principle 5: Make comparisons

Collect data from families both before and immediately after they receive support from early help services. Then follow up to see whether changes are sustained. Make strenuous efforts to follow up with as many families as possible: even if they drop out of receiving services, they can still contribute data to the evaluation. Carry out statistical testing on whether the difference between the ‘before’ and ‘after’ data is significant, or if it is likely to have been due to chance. Going further, recruit or statistically construct an appropriate comparison (‘control’) group who do not receive early help, ideally through randomisation.

Principle 6: Follow through

Be open and transparent by publishing your findings, and acknowledge the limits of the data and analysis. If your methods do not allow you to make causal claims, do not make them. Provide enough detail to allow someone elsewhere to replicate your findings. Plan to develop and improve the quality of your evidence and evaluations over time, to increase the robustness of your findings.

Act on your findings, implementing the recommendations made in your evaluation reports. The large number of influencing factors and massive complexity within an early help system means that large sample sizes are needed to distinguish real improvements from random changes. Be patient: wait for the number of cases to build up and for long-term outcomes to emerge.

*

By applying these principles, local areas can do a lot to increase their ability to generate high-quality evidence and carry out evaluation. In the run-up to a spending review, there is a window of opportunity for local authorities to improve their evaluation capability, in order to make the case for early help in the period afterwards. It is not easy, but it is possible, though action is needed centrally as well, to put in place the support that local areas need.

At EIF we’ll also be doing what we can to support local endeavours, so that we can develop the evidence base together. This is necessary, for the potential of early help to be converted into positive impact for as many families as possible.