Blog

Language, wellbeing and social mobility

Exploring national and international measures of wellbeing, why we should see language as a crucial component of wellbeing, and the links between language, wellbeing and social mobility.

What is a wellbeing indicator?

The term wellbeing means different things in different contexts. Traditionally, it has been used to describe a positive condition that goes beyond physical wellness to include perceptions of happiness and satisfaction.

Today, international organisations define wellbeing more precisely through a set of indicators which are thought to contribute to the physical and psychological wellbeing of entire populations. These indicators often involve objective and subjective measures of health, achievement, safety and employment which are then used alongside more traditional economic measures (such as GDP) to measure and compare countries in terms of human and financial prosperity.

Examples of wellbeing indicators include those identified by the UK What Works Centre for Wellbeing (WWCW), the OECD and Unicef. The WWCW indicators centre on the public’s views on 10 dimensions (measured via 43 indicators) found to be important through national debate:

- the natural environment

- personal wellbeing

- relationships

- health

- what people do

- where they live

- personal finance

- the economy

- education and skills

- public governance.

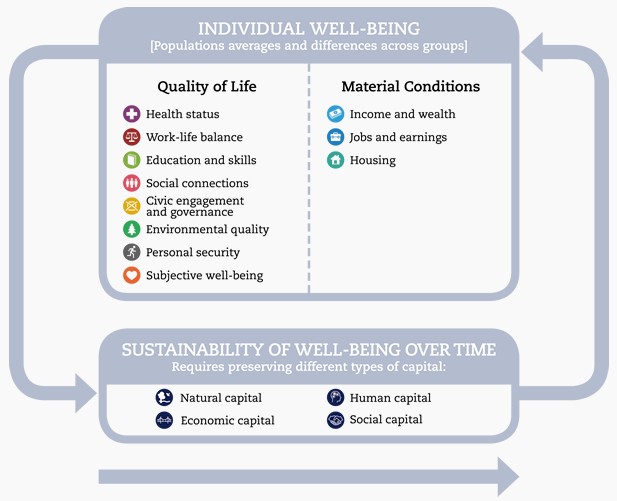

The OECD considers wellbeing primarily through a set of object and subjective indicators selected specifically to measure societal progress:

Figure 1: OECD framework for measuring wellbeing and progress

Source: OECD

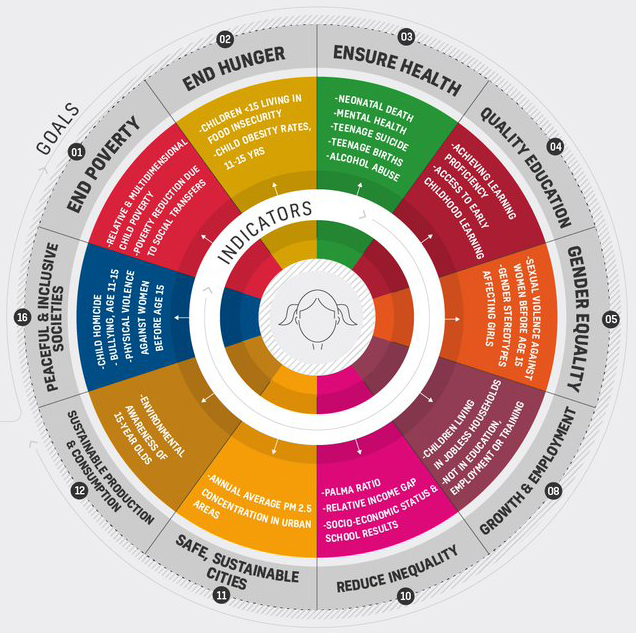

Unicef, on the other hand, exclusively measures child wellbeing through objective and subjective measures associated with the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child:

Figure 2: Unicef’s indices of child wellbeing in high-income countries

Source: Unicef Twitter / report

Each of these frameworks implicitly or explicitly measures social mobility as core indicator. Indicators related to social mobility include children’s overall achievement and attainment, perceptions of work opportunities and the economy, gaps in relative household income and access to employment and training.

The most recent Unicef report card published in June gave the UK scores ranging from low to average on all three of these indices. The UK ranks:

- 19th out of 41 countries in 15-year-olds achieving baseline competencies in reading, maths and science

- 23rd on relative household income (determined by Palma ratios based on the income of households with children in 2014 and 2008)

- 29th for access to employment and training.

Why should child language be prioritised as a wellbeing indicator?

During the early years, language skills form the basis of children’s ability to learn, to understand and manage their emotions and behaviours, and to communicate effectively with others. Once children enter school, language skills remain strong predictors of their academic success and are highly correlated with their access to further education and training and employment opportunities once they enter the workforce.

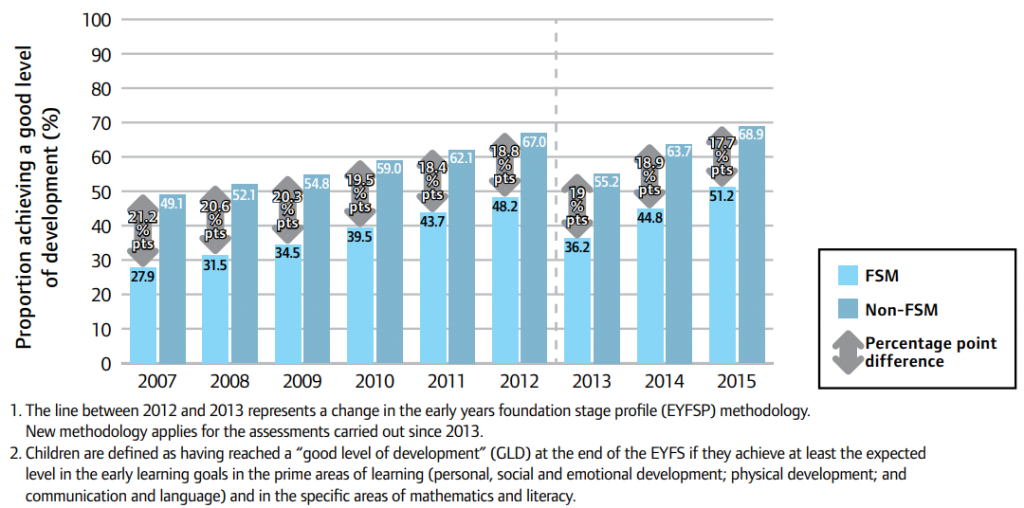

Our report also makes clear that there is a strong and consistent language gap between rich and poor children living in the UK. This gap is already apparent by the time children attend reception and continues to grow throughout their education. Although there is good evidence to suggest that this gap may be narrowing, there is also good evidence there is still much need for improvement.

Figure 3: Proportion of children achieving a good level of development, by eligibility for free school meals, 2007–2015

Source: Ofsted/Department for Education

As we highlight in our report, there is also strong evidence to suggest that this achievement gap is fundamentally underpinned by income-related gaps in children’s language and communication skills, which are already detectable during the second year of life.

Given how important language and communication skills are to school education and achievement, and to future employment prospects, we believe that early language development should be recognised as an indicator of wellbeing for UK children. This proposal is not new, but it is worth reiterating in light of the government’s renewed interest in tackling the achievement gap as part of its broader strategy for increasing social mobility. We view prioritising child language as a wellbeing indicator to be an important first step in understanding this income-based gap and identifying methods for reducing it.

In-keeping with the maxim ‘to improve something, first measure it’, we further recommend that children’s language should be monitored on a regular basis, starting during the second year of life and continuing until late adolescence. While it is clear that some monitoring of children’s language already takes place, we believe that this data could be used more effectively to identify language difficulties so that appropriate early interventions can be made available, and to benchmark progress in this crucial area at the national level.