Blog

Calculating the cost of late intervention in Australia

William Teager led on EIF's analysis of public spending for a new report published in Australia, looking at the costs of late intervention for the Commonwealth and state and territory governments down under. He reflects on how our methods needed to change to suit the new context, and how the report illuminates the challenges facing Australia and its support for children and young people at risk of poor outcomes.

What is the impact of not intervening early enough in children’s lives when things start to go wrong? This is an impossible question to answer fully with a single, simple number. The consequences of not ensuring all children have the best possible start in life are far-reaching and profound, when unresolved challenges can adversely affect a young person’s future health, happiness and prosperity.

One way to make these impacts more tangible, however, is to consider what central and local government spends dealing with issues that could have been prevented or reduced earlier. This includes things like the cost of child protection services; the police, court and criminal justice costs from youth crime; and welfare expenditure related to supporting unemployed young people. Many of these costs have their roots in early childhood trauma and disadvantage.

EIF conducted precisely this kind of analysis in 2016, estimating that across England and Wales £17 billion is spent annually on statutory services and essential welfare benefits for children and young people – much of which could have been mitigated through effective early intervention. While numbers like this don’t convey the full human and economic cost of not prioritising early action, they can help to build the case, making real some of the consequences that failing to address these issues when they first emerge can have for the whole of society for years to come.

This previous analysis, which we repeated for Northern Ireland in 2018, clearly resonated beyond the UK. For the past year, we have been working in collaboration to produce a similar analysis looking at the Australian context. How Australia can invest in children and return more shows the costs to the Commonwealth and state and territory governments of not prioritising early intervention: over A$15 billion a year, which is equivalent to more than £8 billion. It was produced in collaboration between EIF and three Australian partner organisations – CoLab (Collaborate for Kids, a partnership between Telethon Kids Institute and the Minderoo Foundation), The Front Project and Woodside Energy – all of whom share a similar mission to ensure all children, particularly those at risk of adverse outcomes, have the best possible start in life. The report was conceived to help draw attention to the importance of early intervention and galvanise support for an ambitious agenda to improve outcomes for disadvantaged children in Australia.

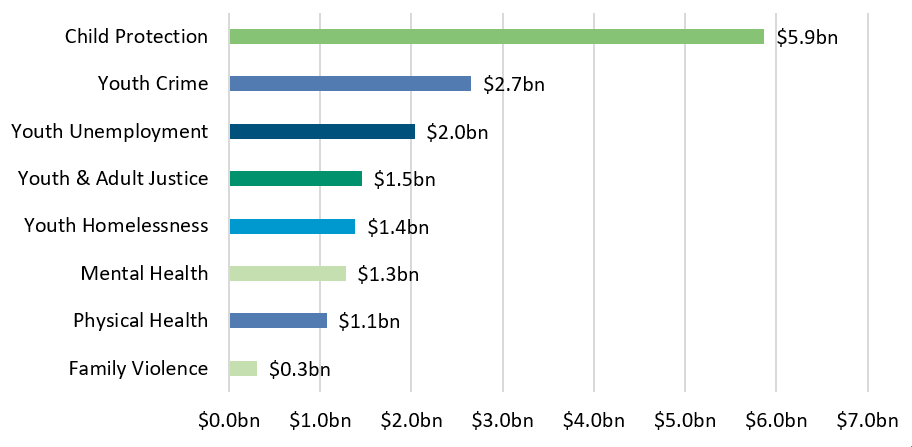

In adapting our methodology, we had to tailor the approach to the specific set of issues faced in Australia: simply repeating our UK analysis would not have reflected Australia’s unique set of circumstances and challenges. This involved an extensive consultation exercise with various local and national experts, and peer review by Australian child policy and data specialists. What’s striking about the report’s findings is their similarity to our findings for England and Wales, in terms of both the relative scale of the cost estimates and the issue areas that are highlighted. Child protection expenditure is by far the single largest area of late intervention expenditure in Australia (as it was here), followed by other high-cost areas such as youth crime and unemployment. However, it is important to note that differences in methodology and data availability mean the two sets of figures are not fully comparable.

Annual cost of late intervention in Australia by issue (2018/19 prices, A$bn)

Both reports also highlight significant local and regional differences in late intervention spending. In Australia, areas such as the Northern Territory and South Australia have significantly higher late intervention spending on a per-head basis than the rest of the country, reflecting the particular challenges faced by remote communities.

While working on this project, we were lucky enough to spend some time based in Perth, holding various workshops, presentations and conversations with local stakeholders, on the importance of effective evidence-based early intervention. The extent of engagement was truly humbling: on some days our schedule stretched from dawn till dusk, from early morning breakfast seminars to evening lectures. It is clear many people in Australia take this agenda very seriously and are keen to learn from the UK’s experience of tackling these important issues.

The report makes a series of recommendations for Australia’s political leaders and advocates to consider, from using current data and information more effectively to support better decision-making, through to actively growing the evidence base by investing in a what works fund for early intervention. We fully support this ambitious programme of activity, and look forward to working with like-minded organisations in Australia to move prevention and early intervention up the social policy agenda. We hope that our analysis, and eye-catching (if simplistic) figures like the $15bn cost of late intervention spending in Australia, can act as a catalyst to shift investment in the right direction.