Blog

The seeds of success? Taking a closer look at new data on the impact of early childcare and education

Max Stanford, head of early childhood education and care at EIF, gives his insight into the most recent report to come from the Study of Early Education and Development (SEED) and what the findings mean in the context of child development.

What is it SEED?

The Study of Early Education and Development (SEED), funded by the Department for Education, includes a longitudinal study which looks at the impact of early education and care, the home environment and parenting on cognitive and socio-emotional development for a cohort of around 6,000 children in England from age 2 through to the end of key stage 1 at age 7. The latest report using SEED data looks at outcomes for children at the age of 5.

Why is it important?

The government is forecast to spend £3.76 billion this year on early education and childcare entitlements, benefitting 94% of 3- and 4-year-olds and 68% of eligible 2-year-olds. As one of the largest investments in early intervention by the current government, it is crucial that we know the impact this is having on child development and reducing the disadvantage gap, as well as how this relates to their home and family environment.

SEED allows us to do this by looking at these impacts on a group of children representative of all children in England of a similar age over an extended period of time. This does come at cost, however, which is why it is crucial to encourage sustained investment in this kind of evidence gathering. Without it, we risk being left with only limited evidence through which to understand the impact of important policies on child development.

What does the latest report find?

The new report looks at the effect of early education and care on child development between the ages of 2 and the start of school at age 5. Overall, it paints quite a mixed picture.

For cognitive outcomes, there is a small but positive association between the use of informal childcare (with relatives and friends) and verbal ability. But there is no cognitive impact for use of formal early education and care (with childminders and group-based early education and care, such as nurseries and play groups).

For socio-emotional outcomes, the report finds a number of poorer socio-emotional outcomes (such as behaviour and self-regulation) for use of childminders and group-based provision. Further analysis suggests that these poorer outcomes are particularly for those using group provision for a high number of hours per week from 2 to the start of school.

What do these findings imply?

To understand these findings, it is important to recognise the context of the wider research, changes to provision, and the findings’ relative impact when compared with home and parenting factors.

Wider research

By comparison with this latest data, previous SEED reports found largely positive effects for group-based provision on socio-emotional development at age 3 and age 4. In part, this difference could be methodological: in earlier stages, socio-emotional measures were recorded by parents; now, at age 5, they have been recorded by teachers, who will come to different assessments of a child’s socio-emotional behaviour. It could also be a result of the child’s transition to school, with its new environment. This requires some unpicking, which we hope will be done in later studies.

Looking beyond SEED data, we see that previous longitudinal studies, such as the Effective Pre-school, Primary and Secondary Education (EPPSE) study, found a strong association between the use of group-based provision and both cognitive and socio-emotional child development, as well as long-term positive outcomes on attainment.

What is key here is that age 5 is not the last time we should assess the impact of early education and care. As found in the literature, short-term impacts can sometimes be seen to ‘wash out’ in later childhood – possibly due to the other confounding impacts of schooling and adolescence – but are found when looking at long-term outcomes such as employment or mental health. It remains to be seen whether the impacts at age 5 will be found in the next SEED report at age 7, and provides grounds to recommend continuing the study into adolescence and adulthood.

Changing provision

It is important also to consider the changing landscape of early education and care. The EPPSE study compared children who had not had any formal early education and care with those that had. Now, however, almost all children use some form of formal provision before starting school. So, by contrast with EPPSE, the SEED data compares with low use of provision. Further analysis in the latest SEED report finds that starting formal provision before age 2, along with over 20 hours of provision per week, has some positive effects for the most disadvantaged. This suggests that focusing on differences solely in the number of hours of provision is perhaps a lower priority. Instead, it points to the need to understand the complex combination of different types, starting points, quantity – and crucially – quality of provision.

Previous research has found strong evidence that high-quality formal provision – even for those as young as 2 and for disadvantaged children – improves outcomes for children. While the landscape has changed and quality since the EPPSE study has improved, SEED has been unable to detect much of an effect, possibly due to the small sample size within SEED. Yet work by Jo Blanden and colleagues using national administrative data suggests that children have better educational outcomes at age 5 if they spend more time in higher-quality provision. This is where work should focus: understanding what drives quality and how it impacts on outcomes.

Relative impact

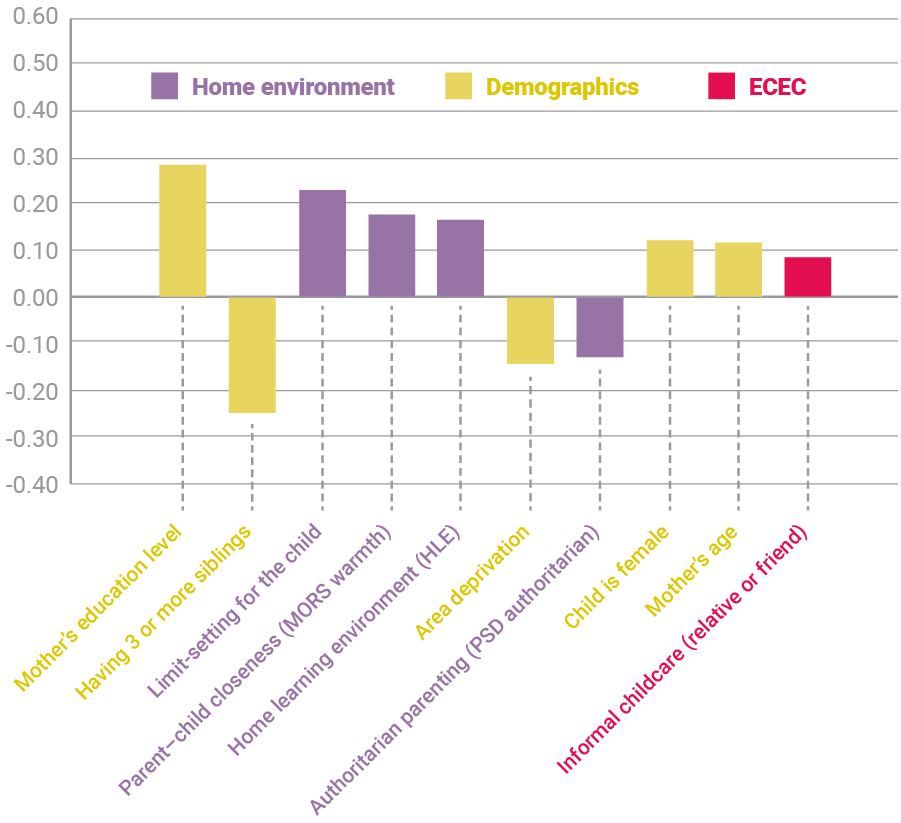

Lastly, it is important to keep in mind the relative size of effects from early education and care compared to other determinants of a child’s development. The SEED report, consistent with previous research, finds a larger positive effect for a strong home learning environment and aspects of the parent–child relationship on measures of children’s cognitive and socio-emotional development. This is illustrated in the chart below, from the latest report, which takes cognitive verbal ability – the only positive outcome found at age 5 for early education and care (informal care, involving relatives or friends) – and compares the relative effect sizes with other home and demographic factors.

We can clearly see that a number of demographic factors, such as maternal education and family size, as well as aspects of the parent–child relationship and home environment, have a relatively larger impact than early education and care. This suggests that efforts to improve school-readiness and close the disadvantage gap cannot be achieved through early education and care alone. A focus is also required on activities, such as parenting programmes, that have evidence of improving the parent–child relationship and home learning environment – and ultimately child outcomes.

The fact that previous SEED reports found that the effects of early education and care and the home learning environment were largely independent suggests that even children in early education and care still stand to benefit from improvements to their home environment.

So where does this all leave us?

The SEED impact at age 5 report marks something of a departure from previous research, providing quite mixed findings. While it suggests there are benefits in terms of better verbal ability when using friends and relatives for care from age 2 to the start of school, it also shows poorer socio-emotional outcomes for children using childminders and group-based provision, particularly when they are in this provision for a large number of hours per week. While some tentative findings suggest some positive outcomes for disadvantaged children when starting provision before age 2 and having moderate amounts per week, it remains to be seen if this will be replicated at age 7.

From this, three implications can be drawn:

- The departure from previous findings and the fact that early impacts do not stop influencing children at age 5 demonstrates the need for more detailed analysis and a continuation of SEED into adolescence and adulthood – as happened with previous studies such as EPPSE.

- Given that almost all children now receive some form of early education and care, we need to focus much more attention on understanding and improving the quality of provision.

- Given the impact of a rich parent–child relationship and home learning environment, we should concentrate on ensuring children have as high-quality a learning environment at home as they do in other early education and care settings.