Blog

Focus on 5: what an international study tells us about children’s early development

Max Stanford, head of early education and care, looks at findings from the new International Early Learning and child wellbeing study (IELS). He reflects on what it can tell us about physical development and persistence at age 5, and the influence of key risk factors, such as low birthweight and disadvantage, as well as parental support for a child’s early learning.

What is IELS?

This is a new international study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This first phase was conducted in England, Estonia and the United States, and overall findings were published by the OECD in March. This week saw the publication of more detailed analysis looking at the findings from England by the National Foundation for Educational Research for the Department for Education.

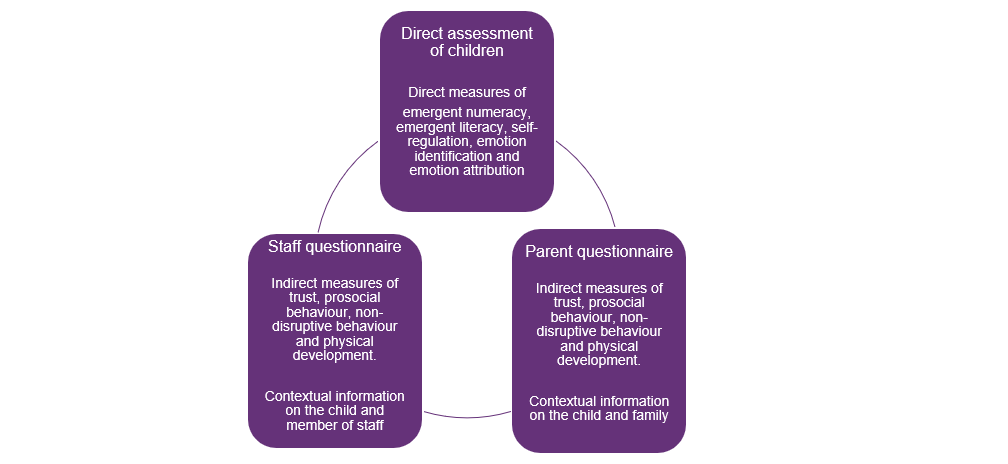

This report, and England’s participation in IELS, is to be welcomed, given the study’s aim of providing a robust understanding of child’s development at age 5, including the influence of certain child and family level characteristics as well as the effect of preschool and the home learning environment. It provides a unique opportunity to generate internationally comparable data using direct assessments of 5-year-olds through tablet-based games and stories as well as parent and teacher questionnaires, as set out in the figure below.

What does IELS tell us about child development at age 5?

By taking a holistic view of child development, the study looks at the associations within and between domains of development. For example, it found that emergent literacy was strongly related to emergent numeracy, both of which were associated with self-regulation as well as a child’s empathy.

This demonstrates the interwoven nature of child development domains, and emphasises that they are not discrete and should not be viewed in isolation. It also suggests that children who struggle in one domain will likely struggle in another, and provides insight into where these associations between domains are stronger. This points to the need to use interventions which support children’s development in multiple domains that are strongly correlated with each other, as highlighted in the example about literacy, numeracy, self-regulation and empathy.

Measuring persistence and physical development

In England, the study measured two additional elements of early child development. The first, physical development, was found to be correlated with cognitive development and many elements of social-emotional development. There was a strong association between economic disadvantage and low birthweight, and poorer physical development, illustrating the need for further work to identify interventions which might mitigate these detrimental impacts.

The second, persistence – the extent to which a child continued his or her course of action in spite of difficulties or obstacles – was found to be positively associated with all other areas of development assessed, particularly positive social behaviour, trust and physical development. In light of other research on the impact of persistence on older children’s outcomes, support for children’s persistence at this age could be an avenue of development for future interventions.

The impact of low birthweight and socioeconomic disadvantage

The IELS report highlights the powerful impact that low birthweight has on physical and cognitive development, as well as working memory at age 5. These findings provide additional evidence on the importance of intervening to address some of the triggers of low birthweight, such as smoking and substance abuse, poor maternal mental health or inter-partner violence during pregnancy. Low birthweight could be an important risk factor to be identified by early years practitioners and schools.

Socioeconomic disadvantage was another prevalent risk factor associated with lower development in almost all measures within the IELS, and this association was strongest for physical development. This is particularly worrying given the limitations that the pandemic has placed on children’s physical activities.

Thinking more broadly about parental support for children’s learning

The IELS found that having parents who engaged in children’s learning more frequently (such as helping them to read sentences) and had more learning resources (such as books) was associated with higher levels of cognitive, self-regulatory and social-emotional development – even when accounting for socioeconomic disadvantage. The study also supports previous research finding that parental emotional sensitivity (such as more frequent conversations about their child’s feelings) is associated with greater empathy and emerging literacy in the child. Additionally, parental engagement in their child’s schooling (such as attending parents’ evening) and attending special or paid-for activities were associated with higher cognitive and social-emotional development.

This suggests the inclusion of these broader elements of ‘home learning’ in efforts to support early home learning, such as the government’s Hungry Little Minds campaign. It also points to the need for a focus on what makes a comprehensive home learning environment, particularly in light of the growing evidence of its inequality during the pandemic.

These findings are perhaps even more salient given the limited relationship observed between early childhood education and care (ECEC) and child development at 5. As argued in the Study of Early Education and Development (SEED) age 5 report, this possibly reflects the almost universal participation in and increasing quality of ECEC, in addition to early school experience possibly enabling those who had less preschooling to catch up. Nonetheless, these findings should not be taken to suggest the negligible impact of ECEC, given the strong impact found in previous research and particularly in light of the recent Ofsted report highlighting the detrimental impact that the loss of preschool has had for some children in the current pandemic.

Where to next?

These findings form part of the study's first phase and we are keen to see IELS develop and include more countries in subsequent phases.

This isn't about creating international league tables of child performance. It's about a clear opportunity to allow for detailed international comparisons of child development at this age, to help understand whether the strength of association between risk and protective factors varies between countries. This would allow us to ask important questions. Is the impact of economic disadvantage more strongly felt in one aspect of a child’s development than another in England as opposed to other countries? And what does this mean for supporting children throughout their development?

Acting on the answers to important questions such as these could go a long way to helping support children’s early learning and their long-term wellbeing.