Case study

Walsall: Developing a theory of change for local reducing parental conflict support

This case example is part of EIF’s ongoing work to showcase how local areas are introducing change, adapting their strategies and changing the way they work to reduce parental conflict and improve outcomes for children.

This is Walsall's story about developing a system-wide theory of change for their reducing parental conflict work with the support of EIF, as phase two of a four-phase reducing parental conflict evaluation project. It is told by Georgina Atkins, Walsall’s parenting lead for Early Help, and Helen Burridge, research officer at EIF.

Find out more about our series of case examples or submit your local area's story.

Our starting point

Walsall is a metropolitan borough located in the West Midlands. In Walsall, one in three children aged 16 years and under come from low-income families, which is higher than the national average of one in five. The high and increasing level of child poverty puts additional demands on our services in Walsall, including parental relationship support services.

To support families with parental conflict, we have a system-wide approach with multiple agencies involved. We wanted to explore how the different activities in our support offer relate to each other and what their collective impact might be for children and families. Therefore, as part of our reducing parental conflict evaluation support project with EIF, and after we had completed our workforce survey, we set out to develop a system-wide theory of change.

The action we took

The first step was to develop an initial draft theory of change for our local arrangements for reducing parental conflict. In my role as parenting lead for Early Help I worked through a series of questions with EIF’s support. We started from our primary outcomes and mapped backwards to establish what was necessary to reach the end goal:

- Why is the support needed and necessary?

- Who is the support for?

- What will the support do?

- What assumptions and enablers should be tested?

- What are the short-, medium-, and long-term goals?

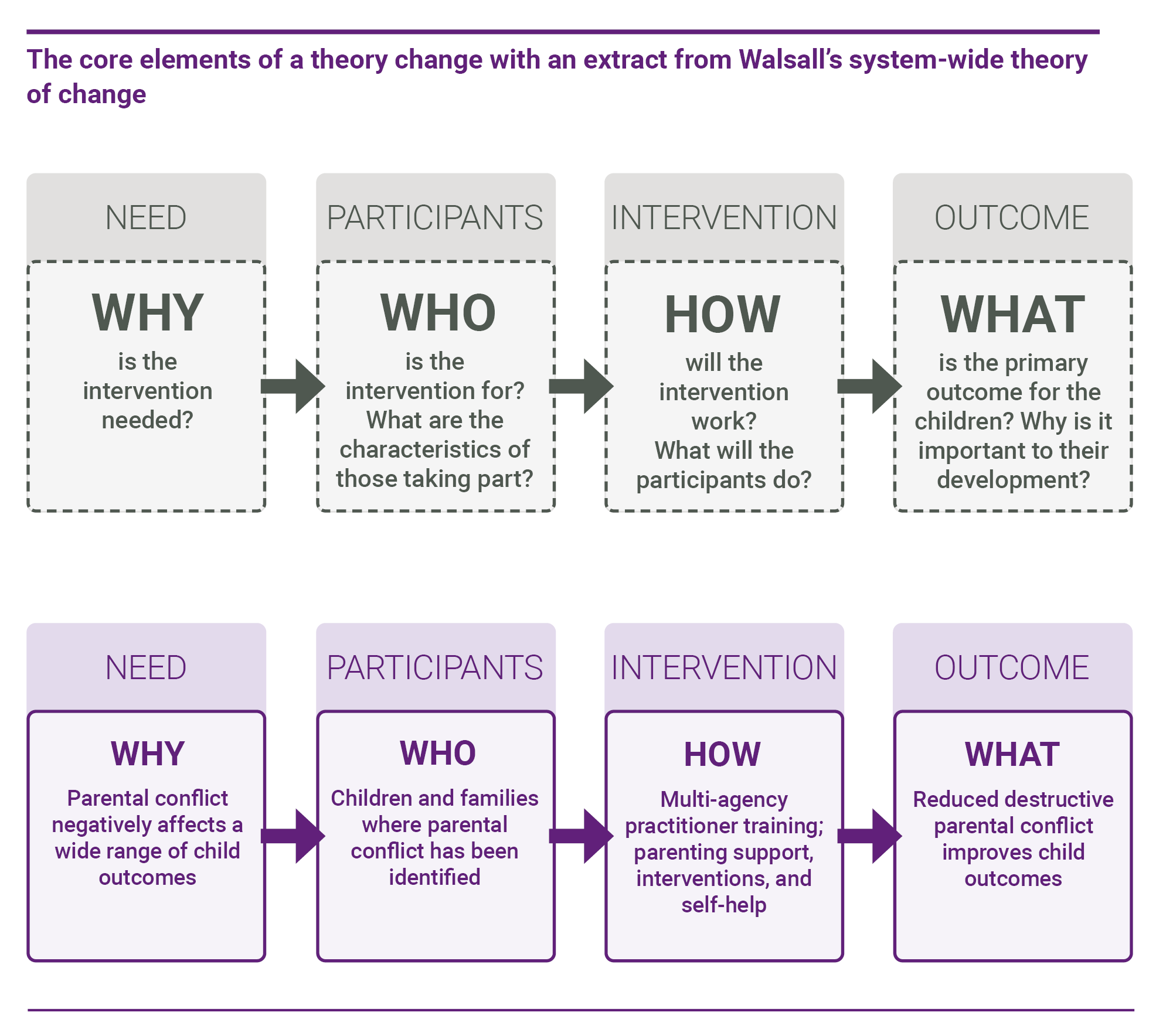

We used the answers to these questions to complete a diagrammatic outline of our theory of change using EIF’s template to summarise the key elements. The theory of change needed to be system-wide, so it considered all activities aimed at reducing parental conflict in Walsall. This includes support that works directly with parents, such as our locally developed healthy relationships virtual parenting course and our Black Country practitioner toolkit. Our support offer also includes a number of indirect activities, such as our training offer for frontline practitioners, senior leaders, and multi-agency professionals working across public, voluntary and community services.

As it is important for a theory of change to be evidence-based, we drew on different forms of evidence when answering each of these questions. This included local data on population needs, the findings from our workforce mapping survey, and academic research including EIF’s evidence reviews and work on a reducing parental conflict outcomes framework.

I then took the draft theory of change to a wider stakeholder group of senior leaders to develop, test and refine it. EIF led a three-hour virtual workshop for our early help steering group with representation from public health, NHS trust, police, housing, employment, schools, and voluntary and community organisations. In the first part of the workshop we discussed what a theory of change is and why it would be useful for Walsall. The remainder of the workshop involved stakeholders interrogating the draft theory of change, beginning with an assessment of the evidence on why support was needed and who needed support at a family and practitioner/service level. The workshop then went on to map the desired outcomes backwards, from ultimate to medium- and short-term outcomes, linking them to the current set of RPC activities in Walsall.

Information gathered during the workshop was used to refine the theory of change. We wrote it up and shared it for final comments before getting sign off from the group manager in Early Help. The diagram below shows the core elements covered in the workshop and provides an extract from our theory of change.

What we achieved

We developed a theory of change which clearly articulates our reducing parental conflict local support offer.

This helped us to establish a shared understanding of what we were setting out to do to reduce parental conflict in the Walsall context, from both a strategic and operational perspective. This provided a shared narrative and language among key stakeholders within the early help partnership and created greater buy-in to this agenda. It also set the direction of travel for the coming months, by for instance, implementing an online parenting course and delivering free awareness training to all partners and colleagues working with children, young people and their families across the Black Country.

It also helped us to communicate what our reducing parental conflict support does, and how it has an impact in a clear and convincing way, both within Early Help to senior leaders, commissioners, and practitioners as well as to other organisations in Walsall including voluntary and community organisations.

By looking at the combination of interventions and services together, we were able to explore how the different activities fit together and what their collective impact might be. This was then used as a basis for conducting an evaluation plan and a separate theory of change for our online parenting course.

Our work contributed to the development of EIF’s reducing parental conflict evaluation guide, where you can find further information on how to develop a theory of change and the templates we used. We also presented our work at the launch of the guide where we spoke about our experience of using a system-level theory of change in Walsall.

What worked well and what we would recommend

We secured good representation and engagement from partners by extending an Early Help steering group monthly meeting to carry out this work. Holding the workshop online made it easier for stakeholders who were geographically dispersed across the borough or with busy schedules to attend.

Introducing what a theory of change is at the start of the workshop helped to ensure that participants had an accurate and consistent understanding, and EIF presented an introductory video on theories of change. Stakeholders who were unfamiliar with theories of change found it particularly useful to be given a simple example of a theory of change to help familiarise them with the terminology, for example, to understand the distinction between outputs and outcomes.

Presenting a draft theory of change for stakeholders to comment on during the workshop rather than starting with a blank theory of change worked well as it provided structure to the discussion. We emphasised that the draft was just a starting point, and the workshop would be used to interrogate, change and develop it further to encourage stakeholders to give their views, regardless of whether they agreed or disagreed with the initial content. This helped to ensure the finalised theory of change reflected views of all stakeholders and subsequently ensured greater ownership of the end product.

Based on their expertise and experience, stakeholders in the workshop sometimes held different views on what should be included in the theory of change. It was useful to have an external facilitator to provide an independent perspective to help resolve alternative viewpoints among participants and reach consensus. Having an independent facilitator also meant all participants could be fully engaged in the discussion.

It was important to build in enough time and capacity at each stage of development. When drafting the initial theory of change, it was useful to revisit the draft in a series of sessions before the workshop as it allowed time to reflect on the content and ensure we had captured all the relevant detail. It also allowed time to consider the evidence for the assumptions in the theory of change. We needed time after the workshop to reflect on the points raised and amend the theory of change to ensure it accurately reflected conclusions from the workshop as well as the previous evidence gathered.

The future

This was the second phase of our reducing parental conflict evaluation project, which was split into four phases covered in this series of case studies:

- Map the local workforce

- Write local system-level reducing parental conflict theory of change, setting out key outcomes (covered in this case study)

- a) Decide which interventions to evaluate; b) Write intervention theory of change and logic model

- a) Write Evaluation plan specifying research questions and methods; b) Plan, collect, analyse and interpret evaluation data; c) Use of evaluation data

The theory of change was used in the next phase of the evaluation project to develop an evaluation plan and to select suitable outcome measures to test whether the activities being delivered as part of our reducing parental conflict support are leading to the anticipated outcomes identified in the theory of change. This part of the project will be covered in our third case study which will be published separately.

We have used our theory of change to set the direction of travel for our reducing parental conflict support and to consider new areas of work. We are beginning to look at developing a theory of change for our wider early help services. Recently, when developing a theory of change for an early help intervention, I was able to show colleagues how to think through each section in the theory of change and how to apply it to our work. The theory of change helped us structure our thinking around the intervention, and how it fits into early help more broadly.

For more information on how to develop a system-wide theory of change, see module one of EIF’s reducing parental conflict evaluation guide for local areas.

Contact details

- Georgina Atkins, Walsall’s parenting lead for early help.

- For more information on evaluation support contact EIF.